Improving sustainably

At Boehringer Ingelheim, taking responsibility for nature and the climate goes without saying. At the same time, this generates greater efficiency and innovative products.

A little paradise starts right next to the fields. Dozens of birds fly over the dense treetops, blue butterflies flutter about, while a coati trots off. Trees, bushes and shrubs grow together rampantly. Native forest surrounds the farmland of Solana Farm in southern Brazil – although much of it was planted by human hand.

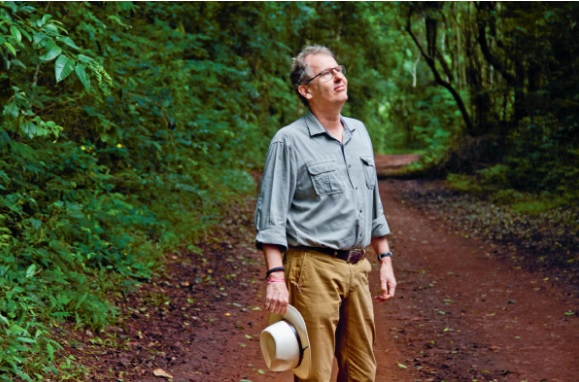

600 kilometres west of São Paolo, Boehringer Ingelheim is cultivating a medicinal plant that can be used to make the antispasmodic precursor for medicines. Erosion makes farming difficult there. “As a result, we decided in the mid-1990s to reforest the steep slopes going down to the water,” says the head of the farm, Adrian von Treuenfels. 70 employees collected seeds and seedlings from native forests, nurtured them to saplings and planted them out – over 193,000 plants to date. 20 years after the reforestation of the initial areas, there are now 176 hectares covered with young forest. “Every year, the reforested area binds over ten tonnes of CO2,” explains von Treuenfels.

While planting trees may not be one of a pharmaceutical company’s main areas of business, sustainability has always been an important topic for the staff of Boehringer Ingelheim. And everyone – society and the company alike – benefits to some extent. On Solana Farm, for instance, medicinal plants are planted along contour line, which provides additional protection from erosion. Any pesticides used are subject to the strictest criteria. This protects the environment and makes the land more fertile over the long term as the ecosystem remains largely intact.

“Today, it is a matter of course that we always ask ourselves: what impact will my actions have, how can we be more sustainable?”, says Dr Andreas Gäbler, who is responsible for the Boehringer Ingelheim “BE GREEN” initiative. Its aim by 2020 is to enable the company to reduce its emissions of CO2 equivalents by 20 per cent for each euro of revenues earned, as compared to 2010. To do this, Boehringer Ingelheim is making whatever savings it can in terms of energy and resources – and not least through its innovations as well as more efficient, environmentally friendly products and processes.

Manufacturing the RESPIMAT® inhaler at the Dortmund facility in Germany is a case in point. In many ways, it has much in common with the distant Solana Farm in Brazil. For one thing, the RESPIMAT® is a device that enables people with chronic lung disease to inhale the medicine SPIRIVA® in such a fine mist that the medicine enters even the small airways. And it is SPIRIVA® whose active substance comes from the medicinal plants on Solana Farm.

But above all, the RESPIMAT® and the Brazilian farm share similarities in terms of innovations protecting the climate. In the 1990s, after the Montreal Protocol came into force, Boehringer Ingelheim management decided to drastically reduce chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) emissions as a result of the damage they were doing to the ozone layer. This meant that a better solution had to be found for the standard pocket inhalers of the day. Since the 1950s, they had contained environmentally harmful propellants that converted the liquid medicine stored in the cartridge into fine droplets. One of the best alternatives available at the time was for the inhaler to deliver the medicine in powder form instead of as a liquid. Boehringer Ingelheim pursues this course with its HANDIHALER® as did other pharmaceutical companies that also switched to powder inhalers. The devices are not ideal for everyone, however, because the patient has to be able to inhale deeply so that the fine powder can enter the lungs.

“At the time, we therefore decided to take a completely new path,” explains Dr Joachim Eicher. He is a senior expert in the RESPIMAT® manufacturing department and co-developed the inhaler’s nozzle for Boehringer Ingelheim 20 years ago. The RESPIMAT®, which came on to the market in 2004, features a spring that forces the liquid medicine through tiny little nozzles under mechanical pressure. This technique creates a mist of around 230 million micrometre-size droplets. It is a technical milestone that also benefits the global climate, as the propellant in standard devices constitutes up to 300 g CO2 equivalent per inhaler, each of which is often only used for a month. “We now save 100 per cent on these emissions,” says Dr Eicher with pride.

Boehringer Ingelheim is continually working towards becoming more sustainable. Many small projects that contribute to reducing greenhouse gases are also of importance here — such as the construction of the “BI5” in Ingelheim, Boehringer Ingelheim’s largest administration building worldwide. It was designed to use as little energy as possible. Heat exchangers recover heat from extracted air. In the summer, the ventilation system cools the space using the cool air that results when water evaporates. In effect, it is an airconditioning system that does not use any additional electricity. The office is heated using hot-water pipes in the concrete ceilings.

Progress is also being made with existing buildings, as another example from the Ingelheim site shows: in the pharmaceutical active substance building, Boehringer Ingelheim has switched the lighting system to energy-saving technology, the cooling systems in the control rooms have been turned up by a few degrees, and heat recovery has been optimised. The result: the building’s energy consumption decreased by around 5 per cent between 2010 and 2012 alone.

Dr Gäbler can now report that Boehringer Ingelheim has been able to decrease its CO2 emissions at its biggest sites by 14 per cent – and that is in relation to the energy consumption to floor space ratio, i.e. the total floor space of all storeys of a building. “We’ve come a long way but we’re not there yet. We have to keep getting better – on every level,” says Dr Gäbler.

The company has also been rewarded for its far-sightedness. A new law came into force in Brazil a few years ago: within a short period of time, 20 per cent of the area owned by farms had to be forested. For von Treuenfels, head of Solana Farm, the new regulation was not a problem. “Thanks to the reforestation project, we had immediately fulfilled the quota.”

-

Adrian von Treuenfels is head of the Solana Farm in Brazil where Boehringer Ingelheim cultivates medicinal plants. -

In the mid-1990s, Boehringer Ingelheim decided to reforest the area of Solana Farm. -

Native forest surrounds the farmland of Solana Farm and provides habitat for numerous animals, such as coatis -

Boehringer Ingelheim takes totally new paths with RESPIMAT®. Picture: assembly in Dortmund, Germany. -

In October 2015, the RESPIMAT® production facility received environmental certification to ISO 14001 standards. Picture: assembly in Dortmund, Germany. -

Boehringer Ingelheim paid particular attention to environmental aspects when building “BI5”, its largest administrative building worldwide.